Conversations that were once along the lines of “wow, psychedelics seem to be a useful treatment for almost any kind of mental health problem” have transitioned to something more like “the psychedelic medicine industry sure has a lot of problems.”

At the heart of this transition is debate about medicalisation, decriminalisation and broader drug law reform. Will making psychedelic medicines legal leave them less accessible when most people who already use psychedelics do so outside of a medical setting? In the short term at least, it won’t. The first psychedelic medicines will be incredibly expensive until the industry achieves significant economies of scale. But will psychedelic medicines mean more acceptance of these substances in the long term? It’s impossible to anticipate the pharmaceutical industry’s impact on drug prohibition and stigma, but we hope so.

Psychedelic law reform is a sensitive issue and people who use psychedelics have been criminalised and stigmatised for a long time. Psychedelic communities are scared this new industry could make things worse, which is a reasonable concern. The legalisation of psychedelic medicine could lead to an even greater crackdown on psychedelics that aren’t used in a medical setting, which is the case for most people who use psychedelics.

Patenting psychedelic medicine

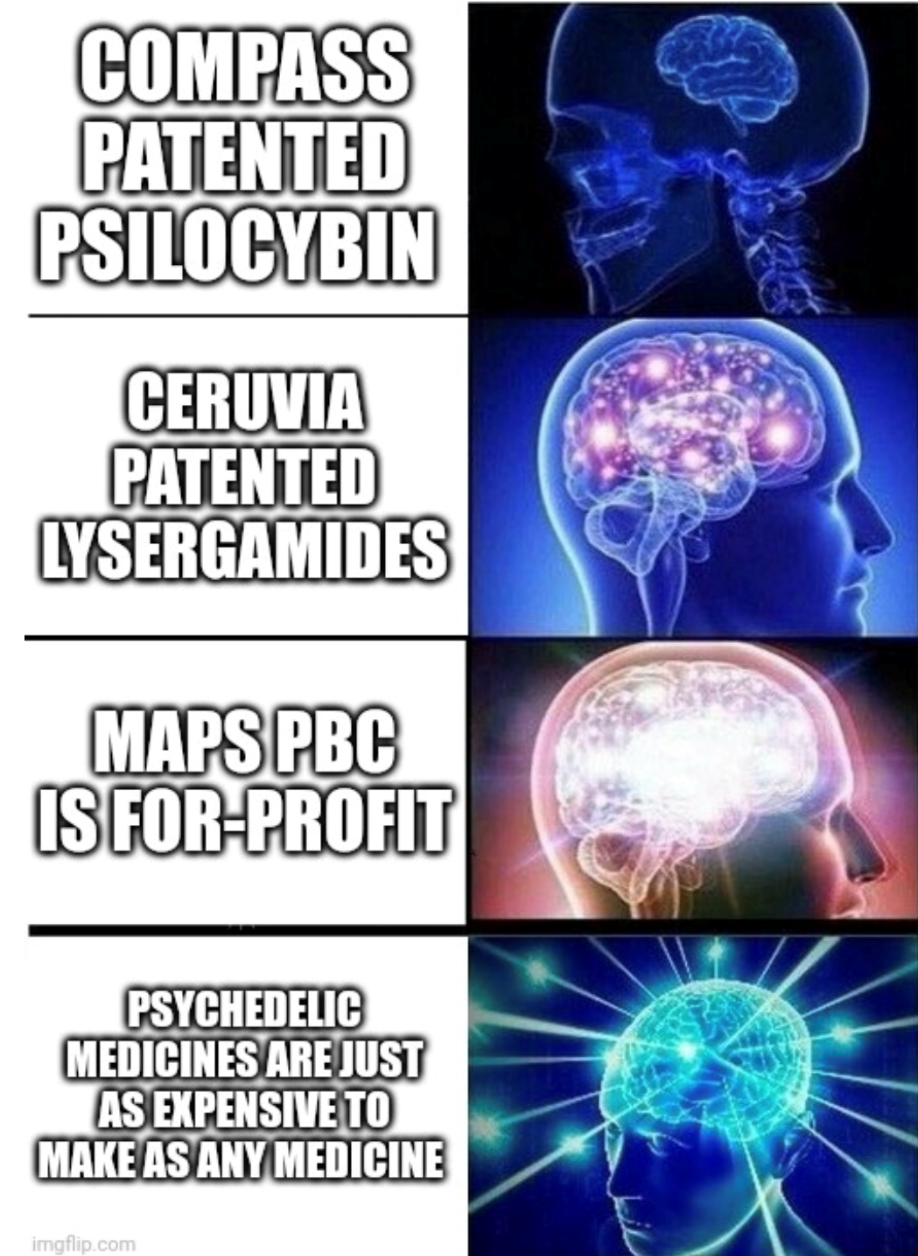

Most people following the recent boom in psychedelic medicine will have heard of Compass Pathways, a company seeking to develop new psychedelic medicines. If so, you’ve probably heard of Compass being criticised for patenting, likely either their patenting of COMP360, a proprietary formulation of psilocybin, or for the use of comfortable furnishings, soft music, and therapeutic touch as part of their psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy.

What most people don’t seem to realise is that patenting is a normal part of the medical industry, and in consumer markets in general. There is no reason to expect that psychedelics would be any different from other medicine in this respect. With cannabinoids, Solvay patented dronabinol (a proprietary formulation of THC); with amphetamines, Shire patented Aderall (a proprietary formulation of four amphetamine salts); and with opioids, Purdue patented OxyContin (a proprietary formulation of oxycodone). Patents are typically as far reaching as possible, and the inclusion of therapeutic touch within Compass’ patent is unsurprising, given COMP360 is administered alongside therapy.

It is expensive to bring a new medicine to patients. It costs around $1 billion to discover a single new drug and complete the clinical trials required to make the drug available as a medicine. Cornering a market with patents and charging premium prices for the first customers is how drug development businesses recoup their costs and continue investing in designing new medicines. It is simply too expensive to design new medicines and give them away for free, even if people need them.

Many corporate players in the psychedelic and pharmaceutical industries are involved in patenting. The problem isn’t Compass or any individual stakeholder – it’s a global economic game that rewards value extraction at the expense of people and the environment. To make a medicine you have to play this expensive game. We know economics is a big problem, but communism didn’t solve anything. Neither will Compass or psychedelics and Compass. Capitalism is clearly a dangerous model for healthcare and social justice, but is it fair to assume psychedelic medicines are going to solve these longstanding issues of inequality? Considering psychedelics as some kind of solution to deeply ingrained human problems reeks of psychedelic exceptionalism; the false belief that psychedelics are somehow more beneficial than other drugs. As with patenting cannabinoids, amphetamines and opioids, the economic context of psychedelics isn’t different from other types of medicine. People who work with psychedelics aren’t better than people who work with other drugs. No drug is good or bad. All drugs are neutral, and psychedelics are no exception.

Anti-Compass sentiment

It is not so much Compass’ patenting activities that are a unique concern, but rather the way that criticisms have been directed at Compass without similar criticisms being levelled at other players. For these other psychedelic medicine players, it’s a good thing that Compass is in the headlights – if Compass is portrayed as the enemy, competitors seem better by comparison.

Hamilton Morris, creator of the Hamilton’s Pharmacopeia docuseries and a chemist at Compass’ Discovery Centre at the University of Sciences in Philadelphia, has commented on his own experiences of the negative sentiment directed at Compass following public criticisms of the organisation. Hamilton describes senior Vice journalist, Shayla Love, as the architect of not only sentiment against psychedelic medicine patenting, but also of sentiment against Compass.

Hamilton noted that throughout Shayla’s criticisms of Compass and the psychedelic pharmaceutical industry, Shayla’s reporting doesn’t acknowledge the for-profit psychedelic drug development company, Ceruvia Life Sciences, only emphasising their not-for-profit arm, Freedom to Operate, who were responsible for bringing challenges of Compass patents to the US Patent and Trademark Office. We reviewed Shayla’s writings on psychedelics, and of the sixteen articles we found that were relevant, Ceruvia receives only passing mention, and this mention is in relation to Freedom to Operate and their opposition to Compass’ patent.

Shayla doesn’t mention that Ceruvia has its own patents on psychedelic medicines, including a formulation of the lysergamide BOL-148 known as NYPRG-101. Compass Pathways, on the other hand, appears in all but one of these 16 articles, with more than 200 mentions in total, alongside relentless criticisms for their patenting activities. The voice of Carey Turnbull, a key funder and stakeholder who joins Ceruvia, Freedom To Operate, Usona, B.more and Port Sophia in a web, also features in Shayla’s works. Hamilton speculates that Turnbull has a vested interest in perpetuating an anti-Compass narrative, which in turn has influenced Shayla’s journalism. Carey is intimately connected with the psychedelic community, but these relationships are not always apparent to the public.

To be fair, Compass’ public relations nightmare around their approach to business began well before Shayla’s writings. In 2018, an article by Olivia Goldhill discussed concerns over Compass’ patents, as well as criticisms of Compass’ transition from a charity to a for-profit organisation in 2016. Compass are accused of misrepresenting their business activities as charitable as a means of attracting collaborators.

Community, industry and drug law reform

With a not-for-profit model, it has taken more than thirty-five years for the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS) to almost make MDMA available as a medicine. The Heffter Institute has been funding psilocybin research at Johns Hopkins University for over twenty years. Extensive research had taken place before Compass’ founders had even found the psychedelic scene. The hard work of the psychedelic community has paved the way for more rapid psychedelic medicine approvals in the future, but successful advocacy has attracted opportunistic outsiders. Compass are new to the psychedelic space, but for them the for-profit space is old hat. With a for-profit model, Compass has almost made psilocybin a medicine, in only a couple of years. The psychedelic community started this medicalisation journey. Just like a trip, we can’t turn back.

The silver lining of this wild west-like time in the psychedelic pharmaceutical industry is an increased rate of change. MAPS has even now formed a public beneficiary corporation with the express purpose of profiting from MDMA, relying on loaned funds and profit sharing. The power of business is unavoidable, and in competing it seems as if we can’t help but gravitate towards the most profitable approach. Compass, Ceruvia and MAPS are all valued within the ballpark of a couple of billion dollars. Big pharmaceutical players are worth much more than this. Pfizer, for example, is worth over $250 billion. It’s still early days and if psychedelic medicines live up to the hype, new and powerful players are still likely to emerge.

While an effective strategy for dismantling capitalism is in no way clear, drug prohibition is clearly one of the larger drivers of systemic inequality in the psychedelic industry, including many of the perceived problems of medicalisation. Pharmaceutical companies working with these drugs can help by supporting drug law reform efforts. Decriminalisation is not enough. Psychoactive substance industries require real regulation outside of medicine. While Compass have expressed some support of decriminalisation, going a step further and advocating for regulated markets could greatly improve their relations with the psychedelic community and make a real social justice contribution, even they think it might be bad for business. The same goes for anyone working in the psychedelic industry; reciprocity can take shape as drug reform.

All the same, if you see Compass as hindering psychedelics because their business operates within a for-profit medical model, consider sharing that energy with some of their competitors, the pharmaceutical industry, or the larger players responsible for creation of such an industry in the first place. When a hospital or clinic is the only place people can access relatively harmless and common drugs, the problem is not just the hospital, the practitioners, or the manufacturer of the drugs they provide. Drug regulations are a complex issue, but outdated drug laws and drug stigma are surely responsible for the greatest drug harms.

Author:

Dr Liam Engel, Adjunct Research Fellow at Edith Cowan University

Disclaimer: The author takes full responsibility for the content of this article.

Want to join in the conversation about this story? Post a comment here.

Journalists that would like to seek expert commentary on drug issues can contact AOD Media Watch who can provide referrals to a range of experts on the issue being reported. Guidelines for journalists can be accessed from our website and resources for the media are available from Mindframe.

Journalist’s Response

Shayla Love was provided an opportunity to respond but declined.